Tell me of Louis

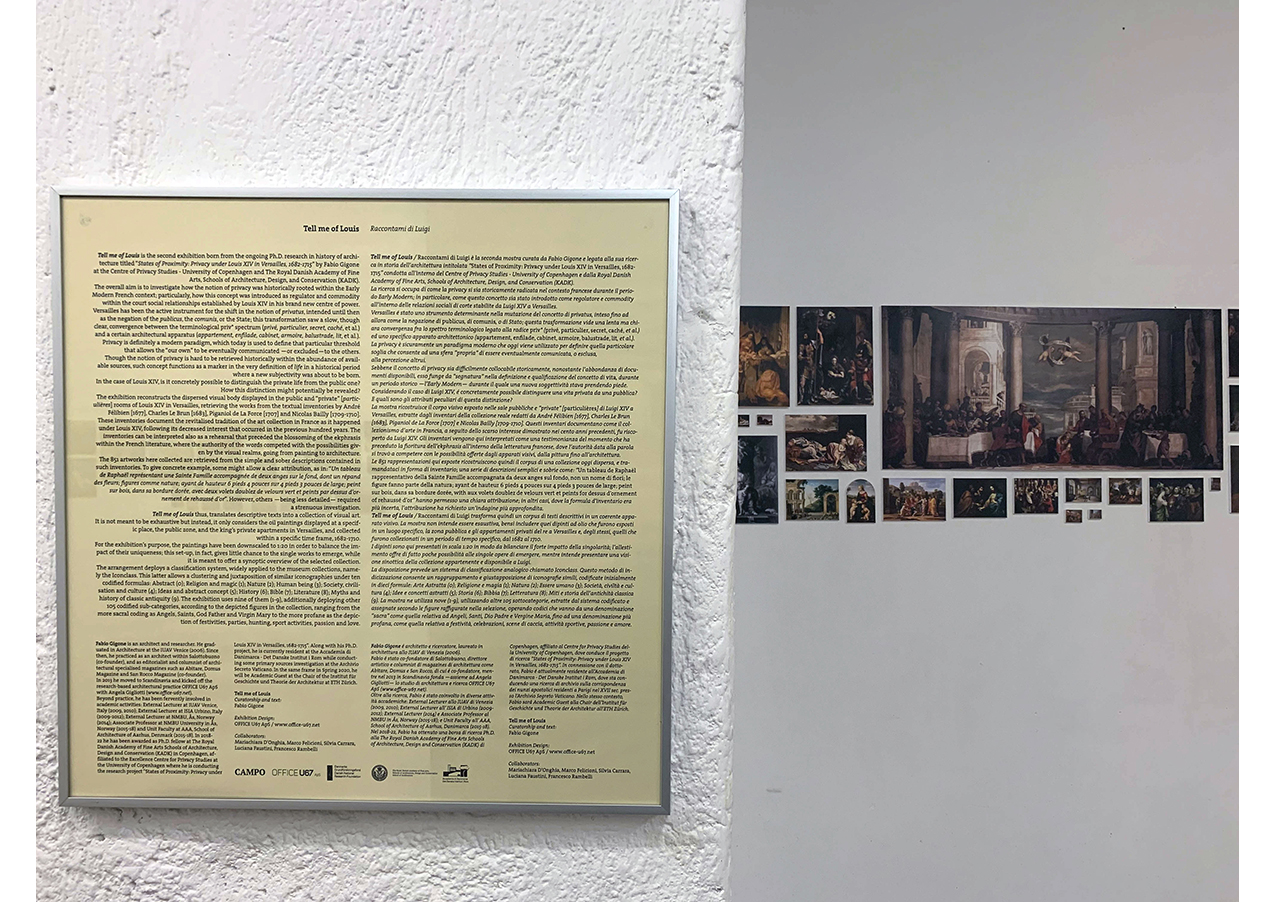

Tell me of Louis is the second exhibition born from the ongoing Ph.D. research in history of architecture titled “States of Proximity: Privacy under Louis XIV in Versailles, 1682-1715” by Fabio Gigone at the Centre of Privacy Studies – University of Copenhagen and The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design, and Conservation (KADK).

The overall aim is to investigate how the notion of privacy was historically rooted within the Early Modern French context; particularly, how this concept was introduced as regulator and commodity within the court social relationships established by Louis XIV in his brand new centre of power.

Versailles has been the active instrument for the shift in the notion of privatus, intended until then as the negation of the publicus, the comunis, or the State; this transformation saw a slow, though clear, convergence between the terminological priv* spectrum (privé, particulier, secret, caché, et al.) and a certain architectural apparatus (appartement, enfilade, cabinet, armoire, balustrade, lit, et al.).

Privacy is definitely a modern paradigm, which today is used to define that particular threshold that allows the “our own” to be eventually communicated —or excluded—to the others.

Though the notion of privacy is hard to be retrieved historically within the abundance of available sources, such concept functions as a marker in the very definition of life in a historical period where a new subjectivity was about to be born.

In the case of Louis XIV, is it concretely possible to distinguish the private life from the public one? How this distinction might potentially be revealed?

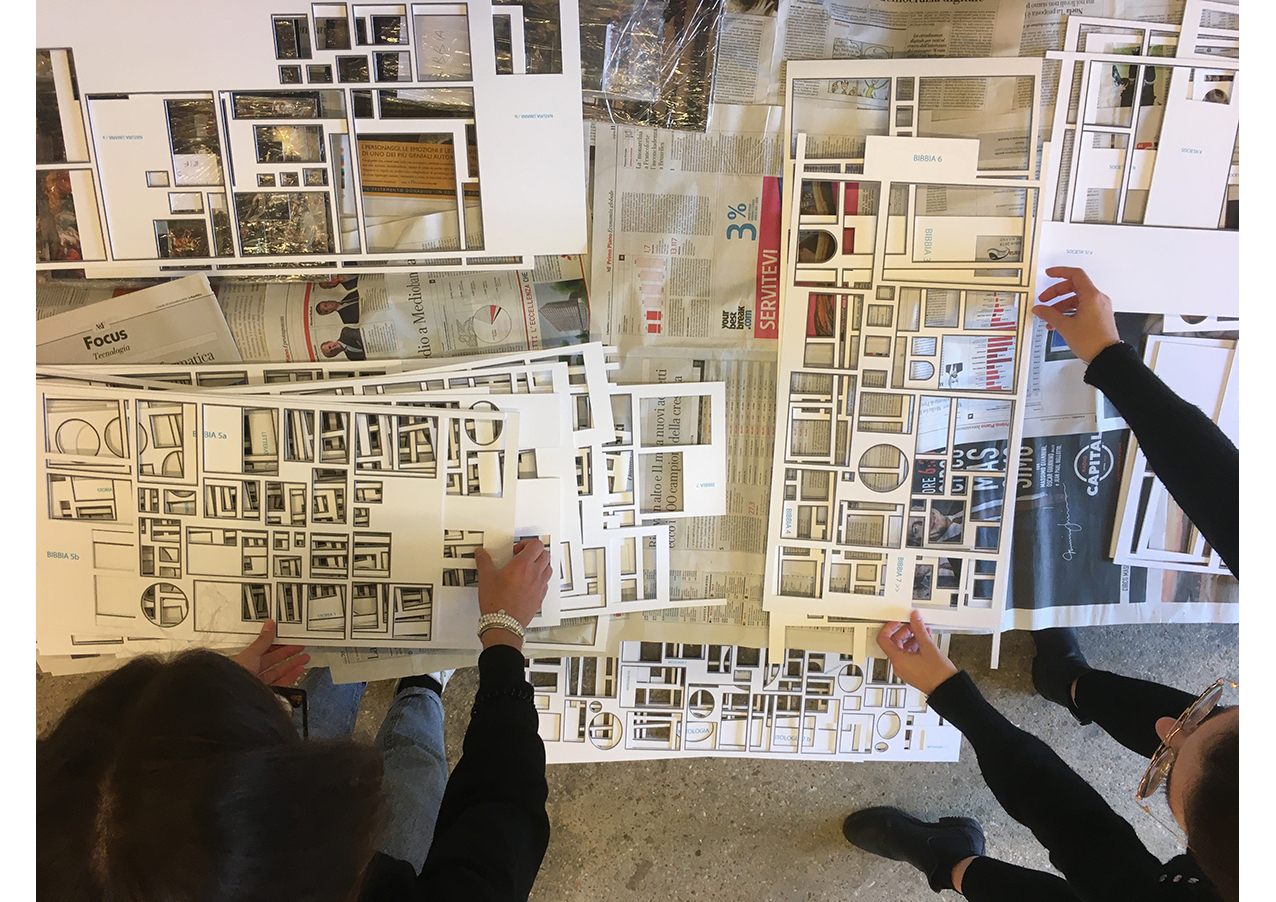

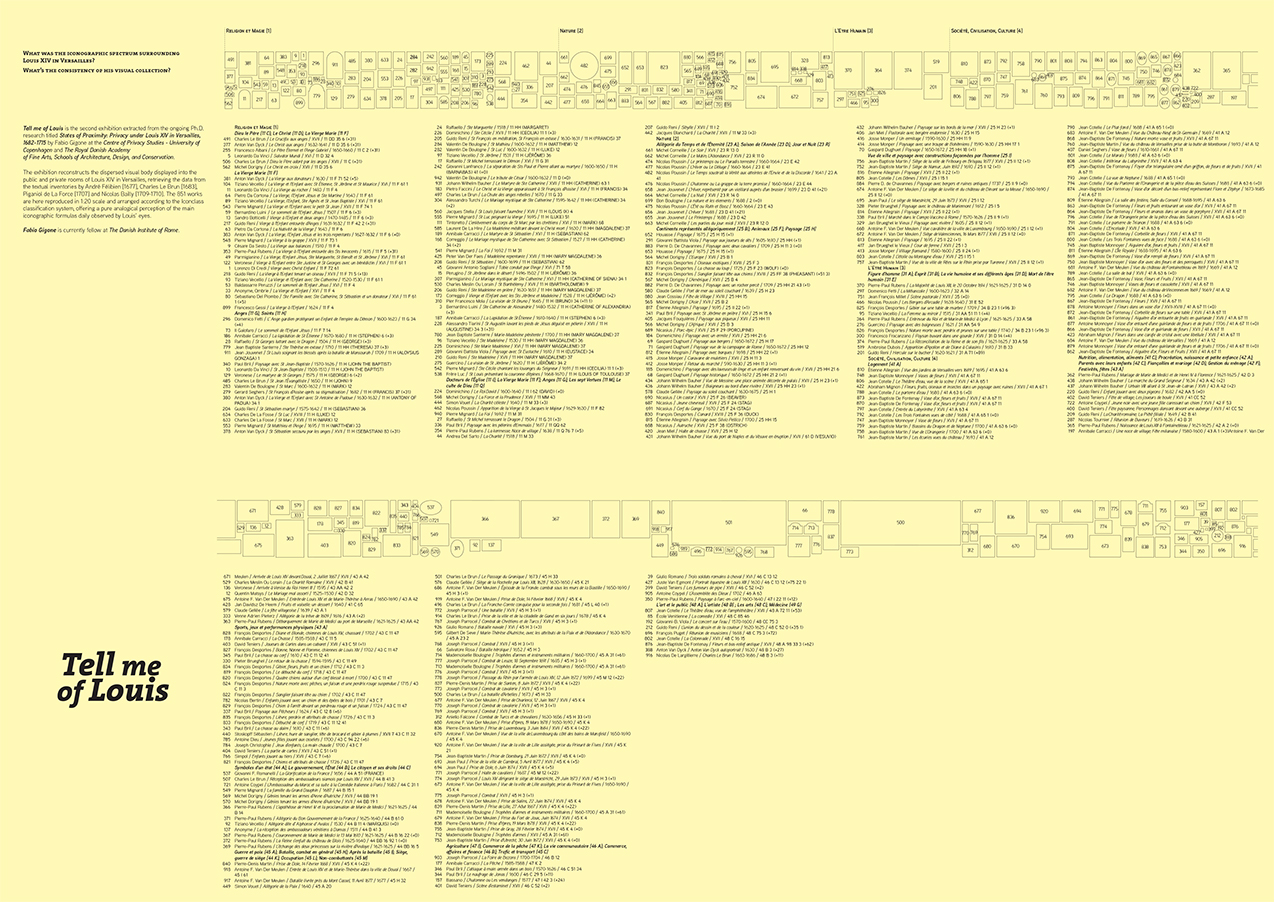

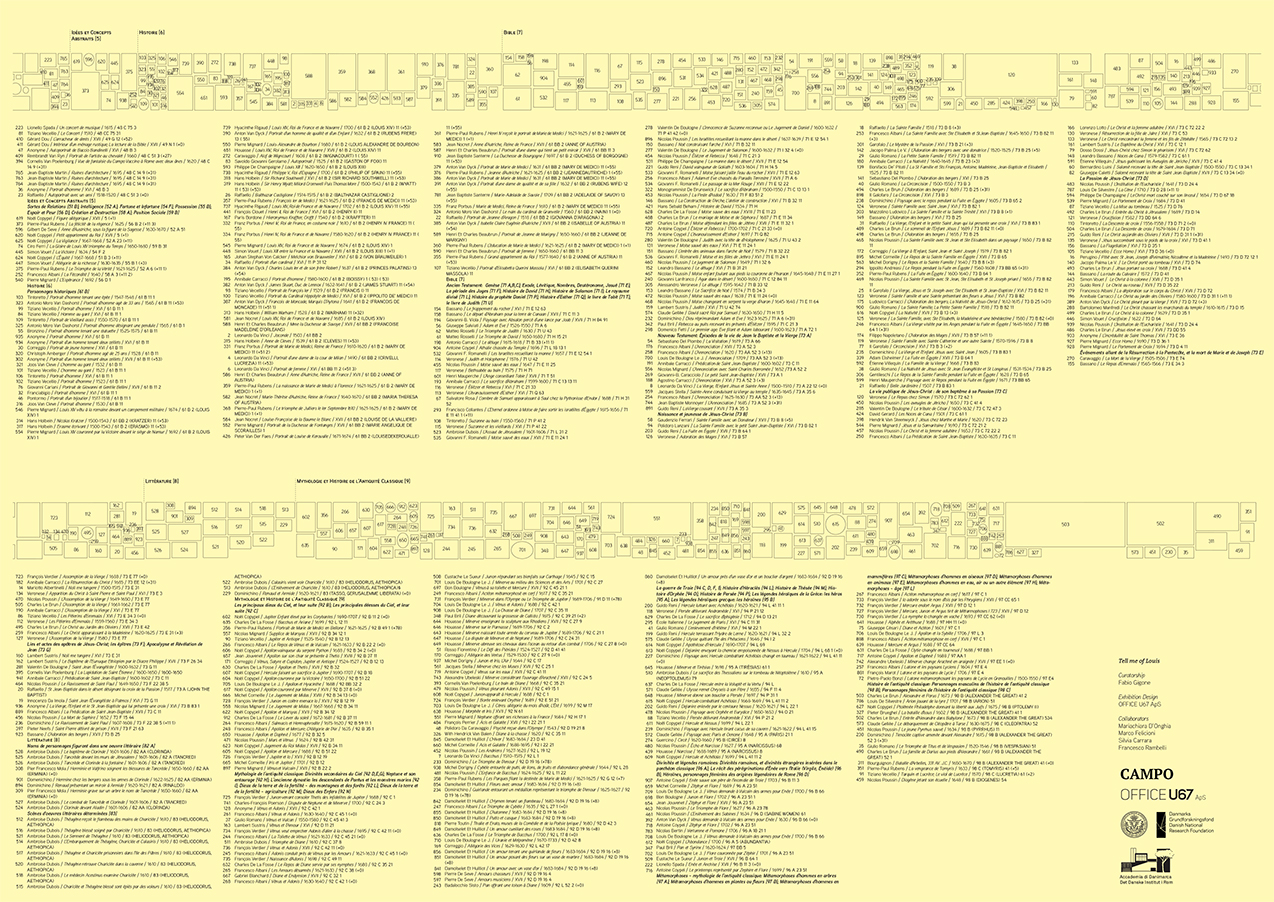

The exhibition reconstructs the dispersed visual body displayed in the public and “private” [particulières] rooms of Louis XIV in Versailles, retrieving the works from the textual inventories by André Félibien [1677], Charles Le Brun [1683], Piganiol de La Force [1707] and Nicolas Bailly [1709-1710]. These inventories document the revitalised tradition of art collection in France as it happened under Louis XIV, following its decreased interest that occurred in the previous hundred years. The inventories can be interpreted also as a rehearsal that preceded the blossoming of the ekphrasis within the French literature, where the authority of the words competed with the possibilities given by the visual realms, going from painting to architecture.

The 851 artworks here collected are retrieved from the simple and sober descriptions contained in such inventories. To give concrete example, some might allow a clear attribution, as in: “Un tableau de Raphaël représentant une Sainte Famille accompagnée de deux anges sur le fond, dont un répand des fleurs; figures comme nature; ayant de hauteur 6 pieds 4 pouces sur 4 pieds 3 pouces de large; peint sur bois, dans sa bordure dorée, avec deux volets doublez de velours vert et peints par dessus d’ornement de rehaussé d’or”. However, others —being less detailed— required a strenuous investigation.

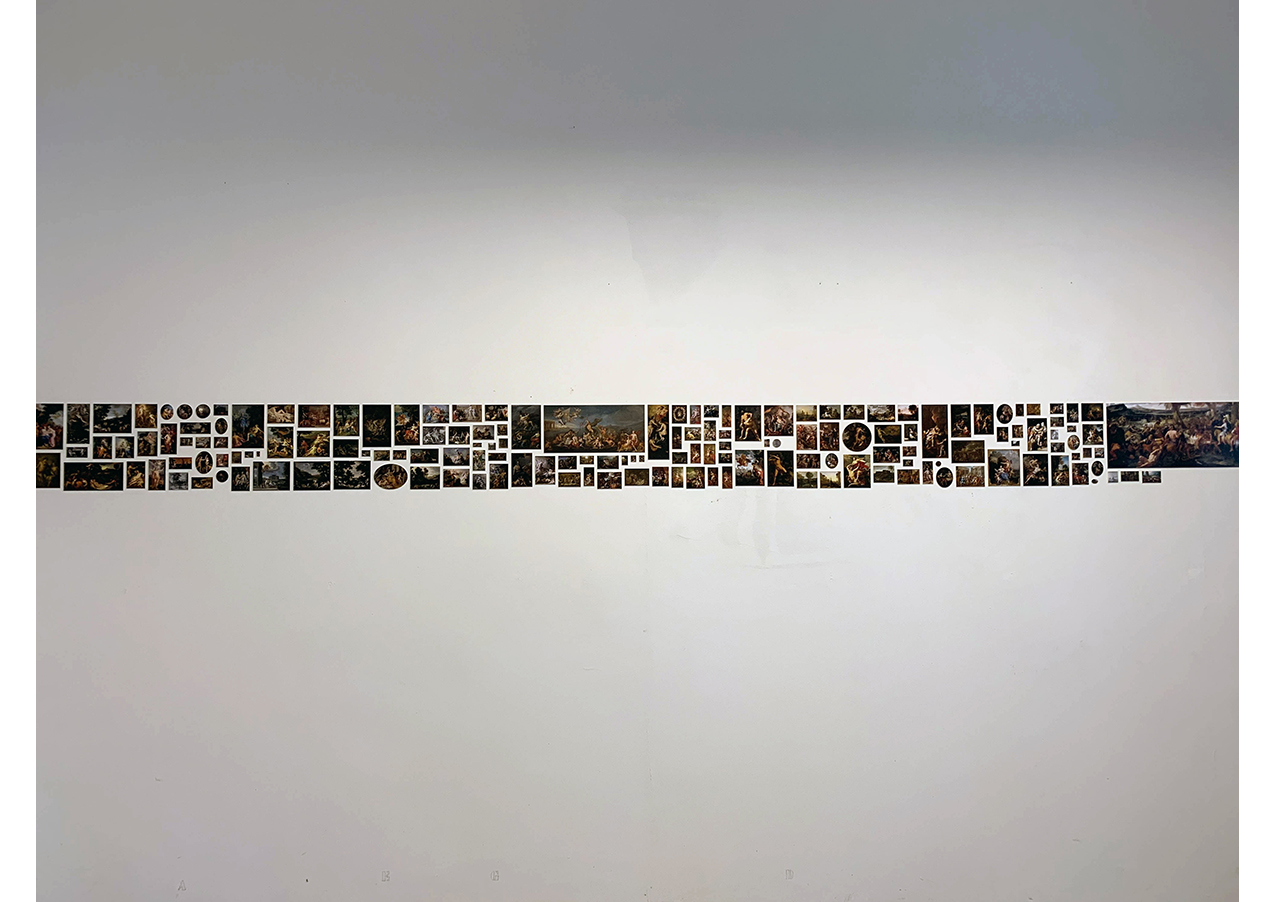

Tell me of Louis thus, translates descriptive texts into a collection of visual art. The collection is not meant to be exhaustive but, instead, it only considers the oil paintings displayed at a specific place, the public zone and the king’s private apartments in Versailles, and collected within a specific time frame, 1682-1710.

For the exhibition’s purpose, the paintings have been downscaled to 1:20 in order to balance the impact of their uniqueness; this set-up, in fact, gives little chance to the single works to emerge, while it is meant to offer a synoptic overview of the selected collection.

The arrangement deploys a classification system, widely applied to the museum collections, namely the Iconclass. This latter allows a clustering and juxtaposition of similar iconographies under ten codified formulas: Abstract (0); Religion and magic (1); Nature (2); Human being (3); Society, civilisation and culture (4); Ideas and abstract concept (5); History (6); Bible (7); Literature (8); Myths and history of classic antiquity (9). The exhibition uses nine of them (1-9), additionally deploying other 105 codified sub-categories, according to the depicted figures in the collection, ranging from the more sacral coding as Angels, Saints, God Father and Virgin Mary to the more profane as the depiction of festivities, parties, hunting, sport activities, passion and love.

Research by:

Fabio Gigone

Exhibition Design:

OFFICE U67 ApS

Collaborators:

Mariachiara D’Onghia, Marco Felicioni, Silvia Carrara, Luciana Faustini, Francesco Rambelli

Sponsored by:

Campo Space

Danish National Research Foundation

The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation

Accademia di Danimarca – Roma

Photos:

AG: © Angela Gigliotti

AZ: © Alessio Zanardo

FG: © Fabio Gigone

MD: © Mariachiara D’Onghia

SC: © Silvia Carrara