Other Tenants

A project by: Fabio Gigone

With: Ludovico Centis, Marco Ferrari, Matteo Ghidoni, Michele Marchetti, Giovanni Piovene

The estate’s inhabitants arrived in the neighborhood before their homes.

In 1968-69 the local council developed a scheme to demolish the district’s original housing nucleus dating from 1951-56. The idea was that residents would quietly “disperse” to other parts of the town. However, egged on by political and student groups, the residents showed unexpected solidarity when faced with the council’s decision and became the driving force behind an authentic save-our-homes campaign. The result was a movement opposed to property speculation that also demanded an end to the district’s isolation. The protest spread to the entire city, culminating in a demonstration in 1972 supported by students, intellectuals, politicians and religious figures as well as the residents themselves.

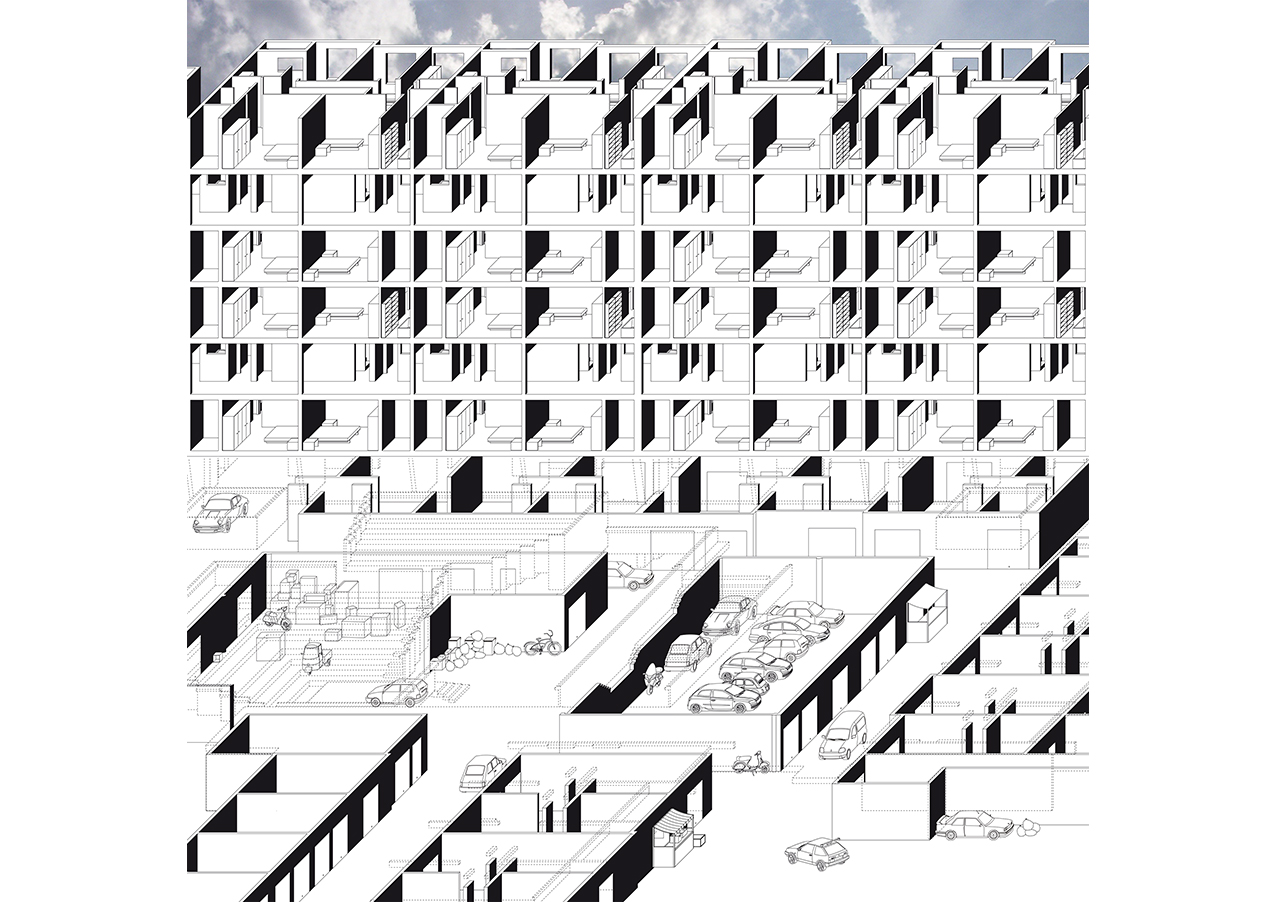

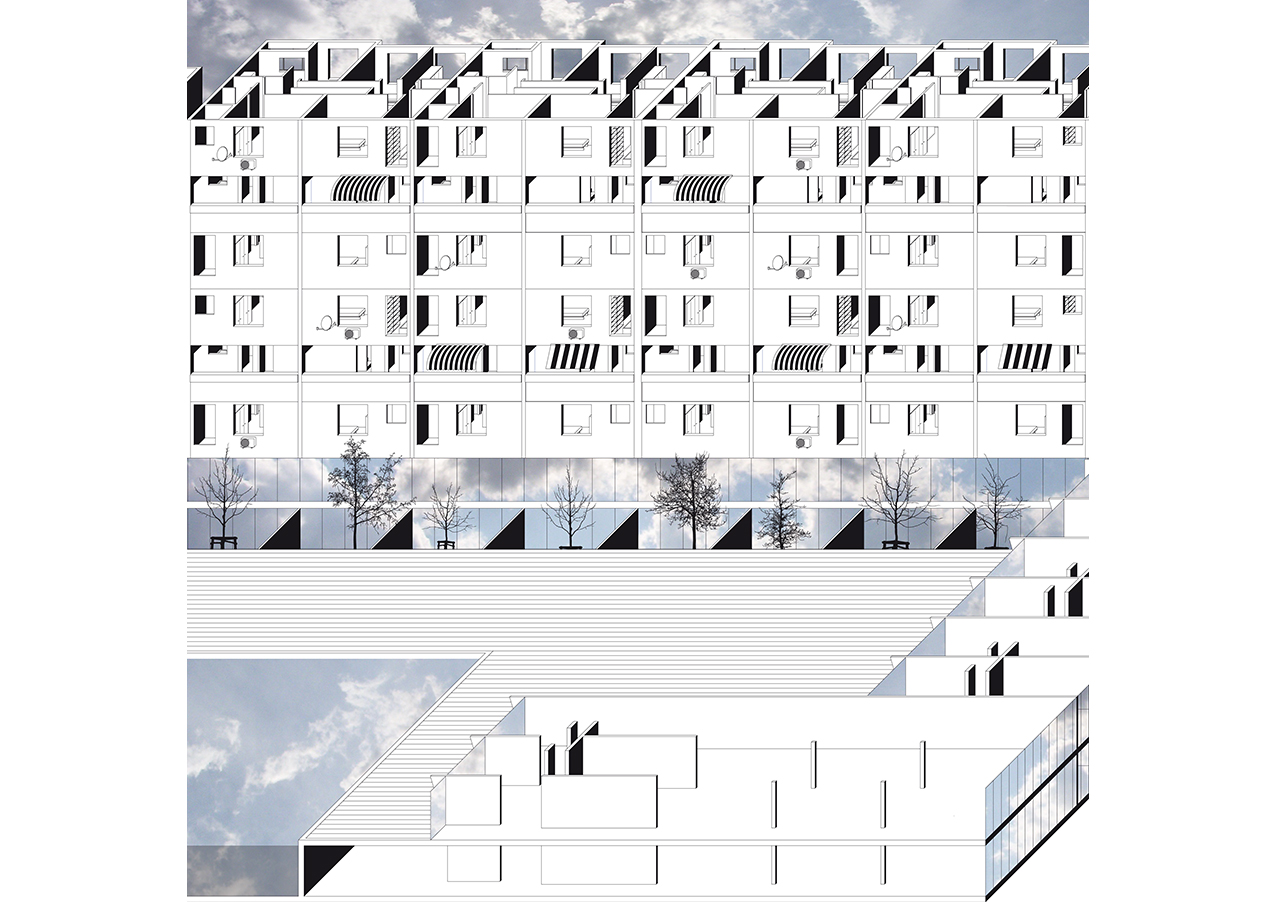

The outcome, in the late 1970s, was the present estate of 265 apartments in 14 buildings of 3-9 residential floors, plus the pilotis and first-level walkway. Nine lift and stair towers join the orthogonally arranged buildings and connect with running balconies on every third floor simultaneously accessing the duplex apartments on those levels and the apartments on the levels above and below them. The ground level has been illegally commandeered by the residents who have created their own garages, storage facilities and small retail outlets. All the buildings are connected by the first-level walkway that forms one large communal space complete with ramps leading to residents’ spaces, a small outdoor theater and a children’s playground plaza. At the moment these communal spaces are so badly run down and inhospitable that they have virtually become no-go areas.

The original tenants are happy with their 5-room (165 or 153 sqm), 4-room (85 sqm) and 3-room (118 or 97 sqm) apartments. The view of the sea from the south-facing rooms is a luxury they all share.

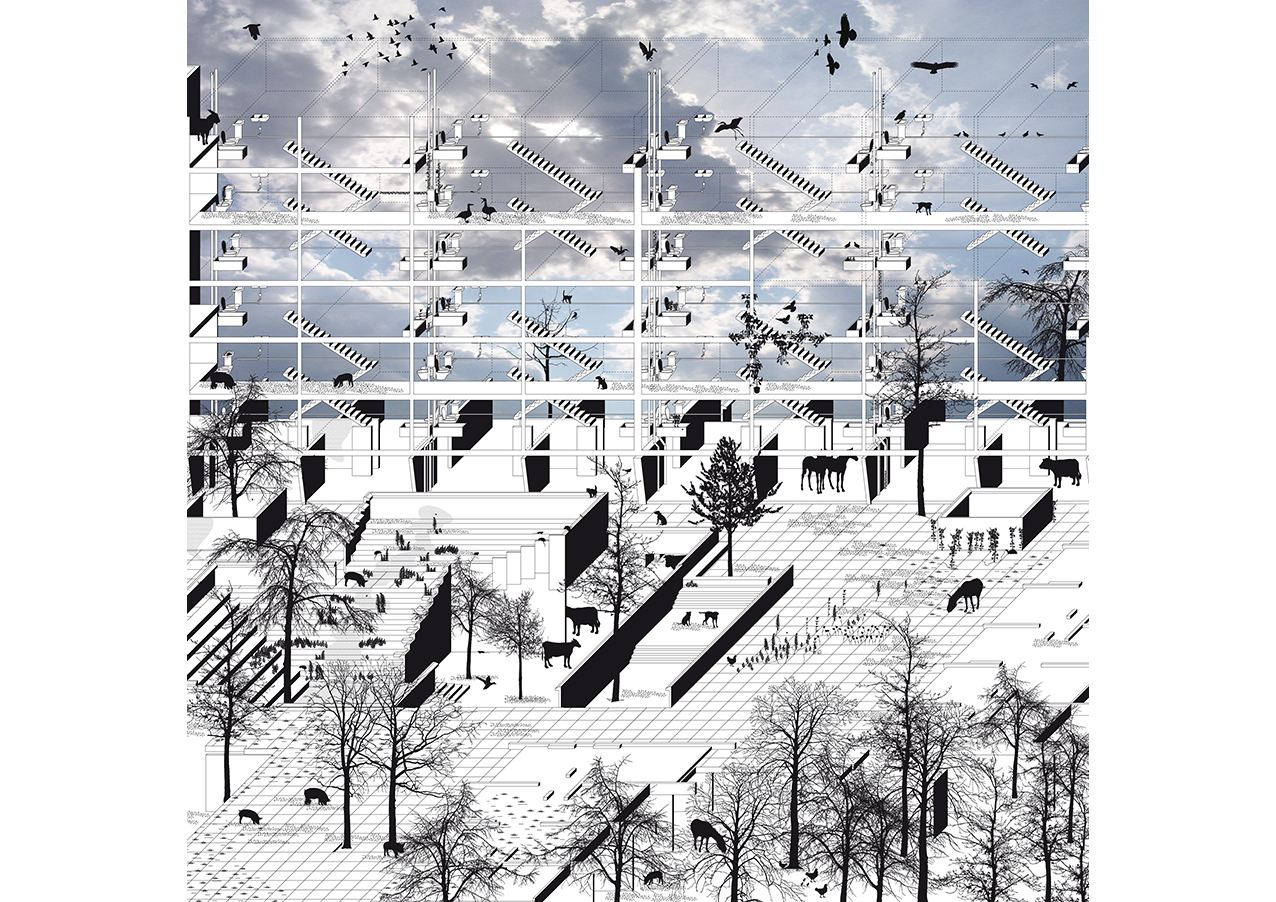

The original tenants all have first and second names. The once-numerous families have shrunk as their members have grown up and gone their own ways. The children, who are fond of the district, have stayed near their parents. These are the inhabitants of the archipelago, the pioneers and now pirates of the expanses between one island and the next.

The new tenants have no names: aggregate figures are used to describe them.

744,425 sqm of land area,1,116,414 m3 of permissible volume, of which 781,490 (70%) exclusively for residential use, giving a total of 11,164 inhabitants once the scheme is completed.

On average they are better off, younger and more mobile than the pioneers. They are expected to raise the tone of the district. They have never acquired the adaptability and the alliance-making and conflict-management skills of the original tenants. On the contrary, they are there mostly because of the large-scale construction projects currently in progress: re-siting a stadium, digging a canal, building a museum. They want easy access to the sea. They aren’t prepared to give up the city and its fabric of streets, blocks, shops and offices. At best they’d settle for a detached house with garden.

The pioneers were seen as a homogenous mass of people. There was a belief in standards. It was discovered that each of them had questions to ask, irreducible needs to be met. Now homes are seen as tailor-made garments for inhabitants to be stitched into. But whose measurements should we take?

Then there are the “others”. Someone eventually remembered them. Some migrated to safer places, or simply vanished, after the last big cleansing operation that coincided with the land reclamation scheme. Others sought refuge in left-over, renegade places still untouched by planning regulations. They adapted to the hard limestone of the Colle, living at first on the clay-and-silt expanse of land reclaimed from the sea. Now that hygiene is no longer THE problem, the question is whether some new form of co-existence between them and us might be possible. Places that have become sterile could be made fertile again. Whether they return or not depends on our willingness to accept diversity, to delight in behavioral variety. Or on the inevitability of abandonment.